Who Was John Calvin?

Like a lighthouse on a high and rugged hill, John Calvin’s theology was the guiding light across the turbulent waves of persecution that would follow for the next two hundred years.

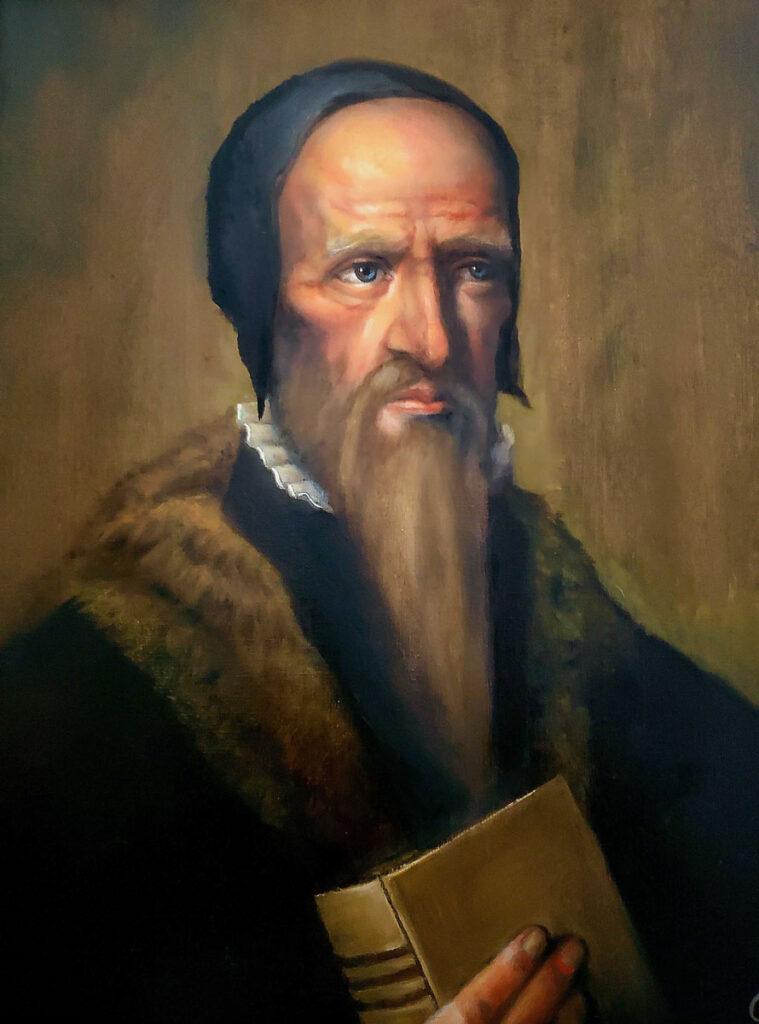

There is no name that shines more brightly in the constellation of Evangelical Reformers than French theologian and pastor John Calvin (1509- 1564). The 16th century, which was the incubator of the Protestant Reformation is still sending light waves throughout Christendom. Like a lighthouse on a high and rugged hill, his theology was the guiding light across the turbulent waves of persecution that would follow for the next two hundred years. Here is history that must never be forgotten otherwise the gospel will end up shipwrecked on the sandbar of good works from whence we were rescued.

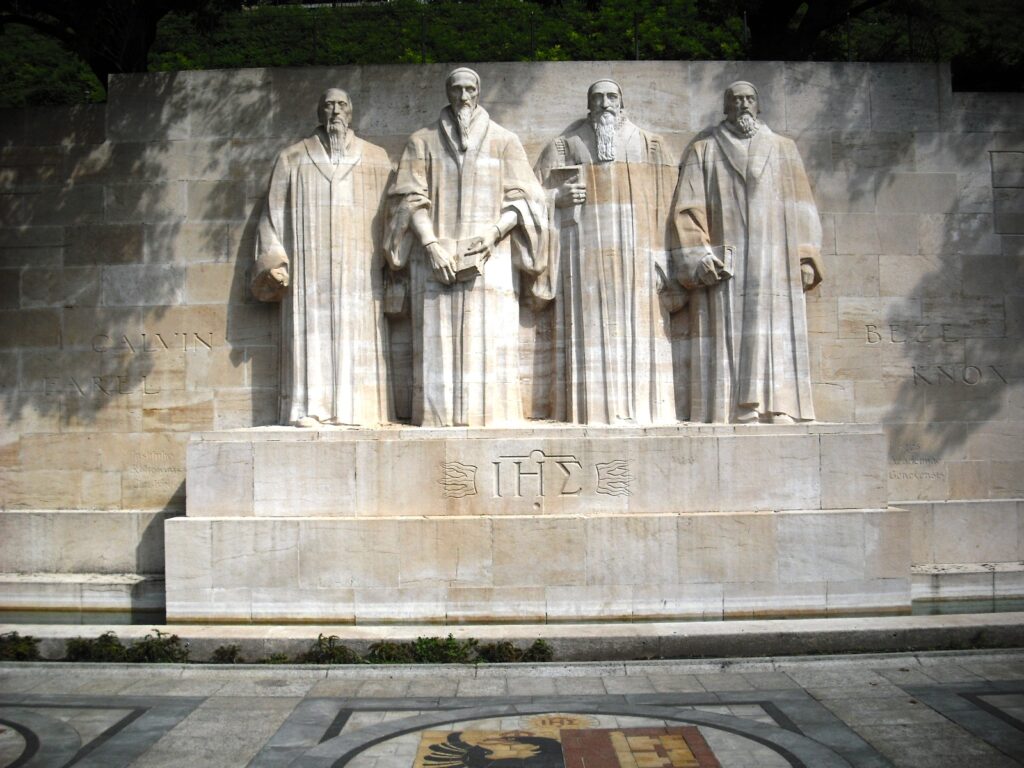

If you could mint a coin symbolizing the Reformation you would have to engrave the mild-mannered John Calvin on one side and the bombastic Martin Luther on the other. Luther, the sound of whose hammer we can still reverberate throughout modern-day Christianity was the plowman. He chopped down the dead trees, tore up the idle ground, and hauled away the roots and rocks and noxious weeds. It took such an iron man and his steel plow to clear the landscape. The gentler John Calvin was not a man of the plow and the ax but a man of pen and paper, an academic, theologian, and lawyer who wrote upon men’s hearts and minds the news of salvation by grace alone and not by works. He proved that the pen is mightier than the sword. Like Luther a generation before him, his conscience was held captive by Sola Scriptura, Scripture Alone.

While religious persecution continued raging through Europe after his death (1618-1648) Calvin’s single pen like a single flame lit a thousand other torches. His commentaries, numerous letters, and sermons started fires of revival burning in Geneva, London, Paris, and Edinburgh. These Reformed Doctrines crossed the Atlantic burning in the hearts of powerful Reformed leaders such as William Brewster & William Bradford. These 1620 Pilgrims boarded a small ship called the Mayflower. With 102 other brave hearts, they braved the dark and turbulent waters of the three-thousand-mile journey to bring the first light of the gospel to the dark shores of the New World.

Before the Pilgrims set a foot on this foreign shore to build a fort at Plymouth, they drafted up the Mayflower Compact. It was a democratic compact. On the world stage, it seemed such an insignificant event. But God forced their ship to land in Plymouth, Cape Cod instead of Virginia which would have put them under the thumb of the king of England. The God who controls the wind and the waves moves in mysterious ways. Here strangers in a strange land had their first taste of Independence from the government. In a dark crowded room, in the hull of an insignificant ship, forty-one men voluntarily signed the Mayflower Compact and democratically voted in their first leader John Carver. This compact became the rocking cradle of self-governance.

This is most important because it was the first legal, democratic document to establish self-government in the New World. Here started the first heartbeat of democracy in an uncertain World. This voluntarily signed compact remained active from 1620 to 1691 when Plymouth Colony became part of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. For seventy years they breathed the intoxicating free air of democratic rule.

No power on earth could now take it from their political DNA. A new nation one-hundred and sixty-six years later would write out its own Declaration of Independence. And it would begin with the same sound of the sound of freedom, “We the people, “ and not with “We the government,” and certainly not with, “I the king.” Boston, a Puritan city on a hill would become a lighthouse to the world.

Ten years after the Pilgrims landed in America, in the 1630’s, many more followed. Reformed Puritans from Britain, and Huguenots from France. Presbyterians from Scotland. Separatists, Independents, and nonconformists of every stripe from the Netherlands, Germany Poland, and Bohemia followed in their wake. The Calvinistic influence was here to stay

Reformed leaders like John Harvard birthed Harvard university in 1636, only sixteen years after they walked ashore into this uncivilized land. Yale, Princeton, Brown, and a ton of others followed and in their wake. The Reformed Puritan clergy was highly educated. They brought the first printing press to America and in 1640 printed the first book which was on the Psalms. The average Puritan young person in 17th century America could read and write. Illiteracy was rare amongst these Bible-reading people.

Politicians like William Bradford, and John Winthrop would set the political stage for righteous leadership. Pastors like John Owen and In-crease Mather would inspire the people to be a light to the world that could never be put out. Evangelists like Johnathan Edwards and George Whitefield during the 1730s and 1740s would set that desire afire. They would begin the first First Great Awakening that shaped the Constitution and America’s destiny.

Though I read Calvin’s Institutes of Christian Religion many years ago I clearly remember how amazed I was at his beautiful prose, his deep devotion, his fear of God, and most of all, the gospel of grace. It was a life changer. It was as beautiful as the bride hearing the voice of the bridegroom. This is why I was not surprised when reading through Will Durant’s “Story of Civilization” for him to make the profound statement that Calvin’s “Institutes” was “one of the ten books that shook the world.”

The beautiful American mayflower symbolizes the Calvinists well. It is a hardy wildflower that grows in clusters and spreads naturally throughout northern and southern Eastern America. In like manner, Reformed theology spread naturally from Maine to Georgia making America a beautiful place to live freely both religiously and politically.

God give us more John Calvin’s.

Dr. Robert P. Bryant

Soli Deo Gloria, “To God Alone Be the Glory.”

Quick Links: