John Calvin’s Life In Geneva

24 Years of Ministry & Service

John Calvin spent most of his life in Geneva, Switzerland. It was in that city of approximately 13,000 citizens, that Calvin did the bulk of his teaching, preaching, and caregiving. It was in Geneva that Calvin served the poor, took in refugees, and taught countless Christians the true faith.

Much has been written, said, and asserted about Geneva and Calvin’s influence there. Many have called it heaven on earth, while many others have claimed that Geneva was a strict totalitarian state that regulated the private lives of individuals. Obviously, somewhere between those extremes lies the truth.

Because there is so much misunderstanding about the history of Geneva and Calvin’s role in it and because the happenings in Geneva have so much influence on life today, we thought that it was important to give this topic its own article. Perhaps by the end of it, we may have a more measured view of history and our predecessors in the faith.

A Few Prerequisites

Before diving in, it will be helpful to set out three key points:

- The Genevan government’s practice of regulating the private lives of its citizens predated Calvin’s arrival.

- The Genevan government’s practice of regulating the private lives of its citizens was not unique at the time. In the 1500s, all governments were doing exactly that. It was not a question of whether religion would be enforced, it was a question of which religion.

- Although Calvin was heavily involved in the government of Geneva, he was only one of many. His word was not law. He abided by the rules in place just like any other citizen.

Life in Geneva

So, what is the big deal about Geneva? Unlike most governments today, the church was heavily involved in the civil procedures and general rule over the citizens. This meant that the church influenced government policy in all spheres. In Geneva, there were laws restricting adultery and drunkenness. There were also laws that regulated marriage, education, and churchgoing. And while some may paint this as a gross abuse of power, a closer look reveals an overarching theme of love and care.

There are a lot of existing records of trials, judicial procedures, and church councils from Geneva that historians continue to sift through today. A lot of the time people will try to pick out a few examples that prove that Geneva’s Christian government was strict and unfeeling, but for every one of those examples, you can find multiple counterexamples demonstrating a true sensitivity to real-life problems and issues. The leaders at the time thought deeply about the proper care for the poor, the uneducated, and the vulnerable. Indeed, the government in Geneva often addressed issues the rest of the world hardly cared about at that time, like the reduction of street fights and the criminalization of abusing children.

While Geneva—as shown in the existing records—was not a sanitized paradise on earth, it was a city whose citizens and government officials strove to do what was best for one another according to the teaching of the Scriptures.

Government Structure

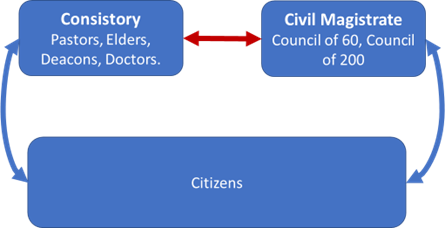

As we mentioned above, the church was involved in the government. This involvement, however, was not totalitarian. Instead, the structure of the Geneva government was essentially split into two main parts: 1) the consistory (or the church council) which was made up of pastors, elders, deacons, and doctors (theologians); 2) the civil magistrate (what we think of as the government today) which was made up of two legislative councils.

Normal citizens were selected to serve in either part of the government on a rotation. In essence, Geneva was a Republic built around and for its citizens. The structure of the government looked a little bit like this:

It should be noted that while the Consistory and the Civil Magistrate worked hand-in-hand, they had different focuses. The Consistory primarily oversaw the examination of new pastors, the proper implementation of the sacraments (discussed here), and the care of the poor. The Civil Magistrate primarily oversaw the punishment of criminals and the general enforcement of laws

The Tyrant of Geneva?

But what did Calvin have to do with all of this? Many have tried to paint Calvin as a tyrant that ruled Geneva through the Consistory with an iron fist. But the reality couldn’t be further from that. Calvin first came to Geneva as a pastor wanting to preach the good news of the Gospel. His massive intellect and heart for others soon led him to draw up a catechism, a confession of faith, and a constitution that the government of Geneva readily accepted.

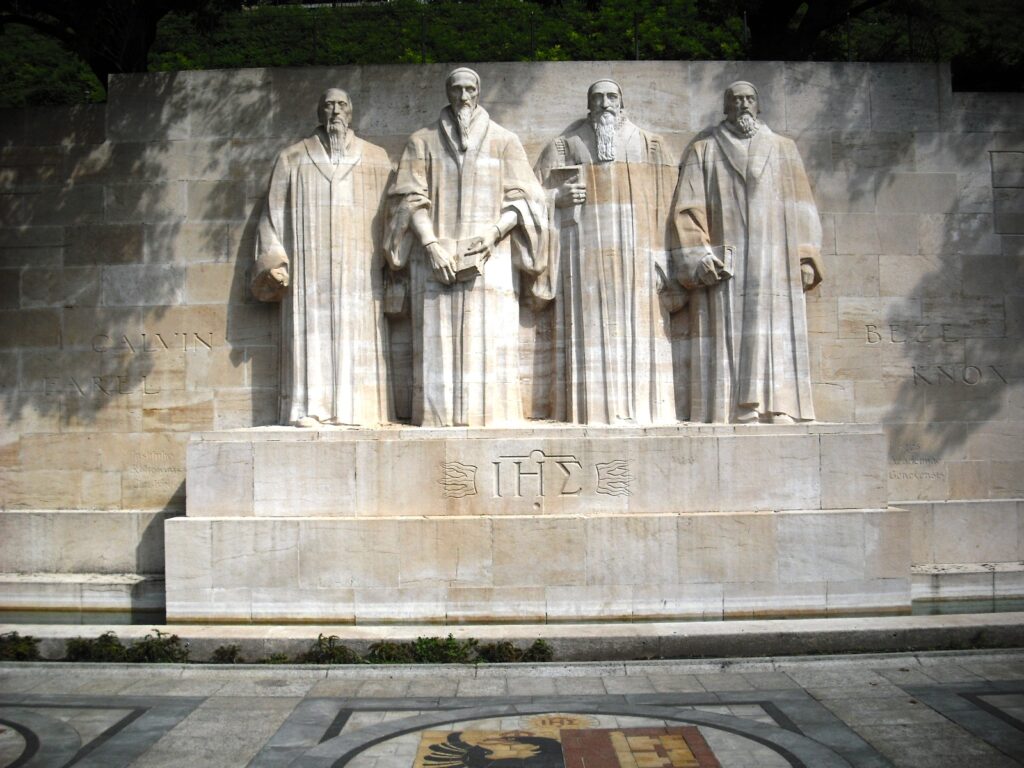

In 1541, Calvin wrote the Ecclesiastical Ordinances and established the Consistory. He went on to become the moderator of the Consistory, however, this did not mean that he had sole power in Geneva. He was consistently checked by the other pastors, elders, deacons, and doctors in the Consistory, as well as the 260 people in the Civil Magistrate. By no means did Calvin do whatever he pleased, but the things he was able to enact had a lasting effect.

Calvin labored to make Geneva a city that would be an example of a flourishing Christian life and a center for Gospel truth. He firmly believed that the Reformation could only take hold in Europe and beyond if people understood and applied God’s word in their everyday lives. Thus, he put a huge emphasis on education. He set up primary and elementary schools that any child could attend, devised a system to teach adults how to read and write, and established the first Protestant university in the world.

The founding of this university was one of Calvin’s favorite accomplishments, as it meant that Geneva’s citizens could be edified by sound teaching. Indeed, people from all over Europe came to study and teach at Calvin’s University, bringing Reformed theology to the popular level.

God’s Glory and Man’s Good

It is helpful to understand Calvin’s Geneva in contrast with the Roman Catholic government at the time. In Calvin’s day, the Roman Catholic ‘magisterium’ had sole rule in many cities, placed unfair burdens on their citizenry, and required the false worship of God. When he wrote the constitution of Geneva and Ecclesiastical Ordinances, Calvin was fighting against the Roman Catholic form of government and hoping to secure a fuller life for the people around him. In Calvin’s Geneva, the government existed to promote man’s good and protect God’s glory.

Man’s Good

During Calvin’s time in Geneva, systems for the care of the poor, orphans, elderly, and the most vulnerable were put in place. There were actions taken against financial monopolies and exploitive prices. In fact, the price of food was so low in Geneva there was hardly anyone that ever went hungry. This was an anomaly in 1500s Europe.

Calvin additionally ensured that all the ministers were trained properly to handle domestic disputes, prevent street thefts, and support local trade. He also ensured that the church would discipline members who oppressed their workers and maintained unachievable working hours. Every place where a person’s life could be improved, Calvin sought and fought for it.

God’s Glory

Alongside all the improvements for the general well-being of citizens, Calvin fought for the purity of the church. He helped create guidelines for the proper worship of God, the teaching of the Scriptures, and the living of a Godly life. Calvin also rooted out heresies and wrote incessantly to clarify any theological misunderstandings.

Furthermore, he helped the Civil Magistrate establish blasphemy laws and outlaw any form of idolatry or corrupt worship. This may seem extreme to our modern ears, but remember what we said at the outset, it is not whether religion will be enforced, it is a matter of which religion will be enforced.

Calvin firmly believed that the proper worship of the one, true God should be prioritized above everything. He believed it was the duty of the Civil Magistrate to protect and defend that worship. He wrote:

“This proves the folly of those who would neglect the concern for God and would give attention only to rendering justice among men. As if God appointed rulers in his name to decide earthly controversies but overlooked what was of far greater importance — that he himself should be purely worshiped according to the prescription of his law,” (Calvin, Institutes, 20.9).

Conclusion

Calvin worked in Geneva for over 24 years, trying to bring about reform in the city and beyond. He never achieved a heaven on earth. Let’s face it, who could? He was far from perfect, but he produced vast improvements in the standards of living and in the purity of worship with lasting effects on Geneva, Europe, and even in the Americas and Africa.

Was Calvin like a Protestant Pope? No—he worked within the system and time that he was in to bring about the change he thought was necessary. He is a good example to us of how to work within our systems today. We will look at this in more depth as we explore Calvin’s impact on the United States in the last part of our series.

All in all, we should remember that Calvin was a man of his context attempting to achieve something new: an unflinching application of the Word of God to every sphere of life. Let us hope to do the same in our lives.

Read more about John Calvin’s doctrines of Reformed Theology

Learn more about the gospel of Jesus Christ and how it can change your life